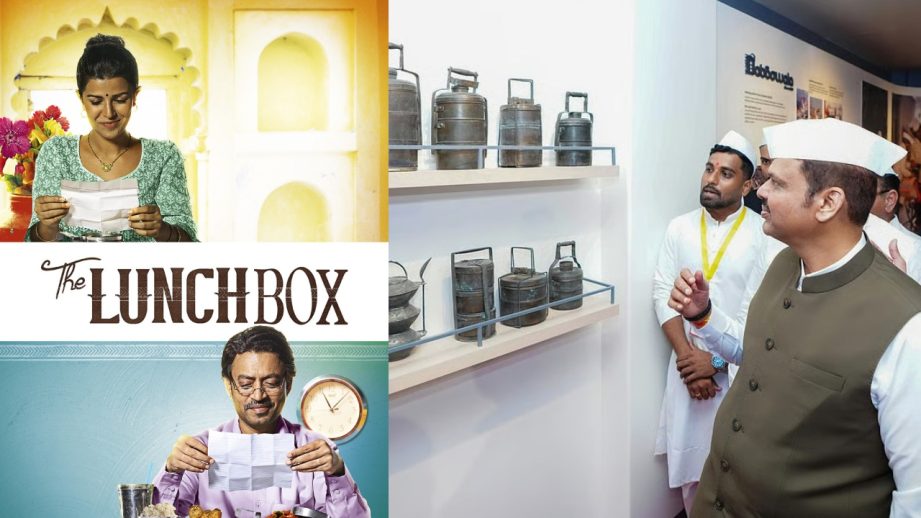

A revisit, long overdue, has finally arrived, and it brings with it memories of a film that collared the heartbeat of a city. The launch of the Mumbai Dabbawala International Experience Centre (MDIEC) in Bandra rejuvenates the tender, stinging story of Ritesh Batra’s The Lunchbox (2013). That film, like the museum now, honoured what had long remained in the background, the quiet machinery and emotional texture of everyday lives in Mumbai.

When The Lunchbox released, it did something rare: it didn’t just tell a love story, it mapped a city’s emotional geography through stainless steel tiffins and handwritten letters. At the centre of its delicate plot was an accidental connection, a rare error in the otherwise near-perfect Dabbawala system that brought together two strangers, Ila and Saajan, through food, notes, and mutual longing. It was the Dabbawalas who enabled this mistake, this miracle. Their presence was not dramatized, nor romanticized and yet they were essential, silent agents of change.

Now, more than a decade later, the real-life Dabbawalas are finally being given their due in the physical realm — with a dedicated experience centre that traces their 130-year-old legacy. The timing feels poetic. The museum’s galleries celebrate the discipline, humility, and efficiency of the Dabbawala community, whose delivery system has baffled management experts and been cited in business schools from Harvard to IIM. But beyond logistics, what is being honoured here is trust — the simple, powerful trust of a city in the hands of its workers.

Much like the film, this tribute is a window into the Mumbai that doesn’t always make headlines. Not the Mumbai of skyscrapers and stock markets, but the Mumbai of suburban train journeys, cramped offices, and small homes filled with the aroma of packed lunches. In both, we find a deep yearning — for connection, for recognition, for small escapes from the everyday.

Batra’s film framed the city’s spaces with care: the railways, narrow lanes, modest kitchens, and the intimate silences of domestic life. The museum now contextualizes these visuals, grounding them in the very real, tangible labour of men who move across this city with quiet precision and unmatched devotion.

Reassessing the Dabbawalas today, be it through the museum’s exhibitions or the after echoes of The Lunchbox, is to reassess an even larger question: in a society that behaves so conspicuously through hierarchy and noise, do we even see those who carry its pulse? While glory may arrive slow, it certainly brings the power of reminding us of the prosaic wonders that create the melody of our life on the daily.