You can’t download a crafting experience.

While you may look up instructions, the digital world doesn’t offer the feeling of a pencil on a sketchpad, wool yarn through your fingers, or shaping clay into a new vessel.

It’s an analog experience that more people are craving: sitting down to create something, meeting a new group of people, or being exposed to new ideas. Hobbies are, in some ways, the ultimate tech-proof activity — and offer a rosier picture of what an AI-future could look like.

“It’s not the kind of thing that you want AI to speed up or improve. The whole value of a hobby is actually you doing it and your personal fulfillment in doing it,” said Diana Lind, an urban policy specialist and the author of “Brave New Home,” a book about isolation and economic woes brought on by single-family housing in America.

Hobbyists and scholars told me that hobbies are an antidote to the perfect storm of affordability concerns, social isolation, and a yearning for life beyond screens. A more sober-inclined, community-starved population is gravitating toward pursuits that get them out of the house and offer them a bang for their buck. Some of the pressures of the AI revolution may simultaneously undergird the push toward a hobby frenzy; workplaces are shrinking, there’s less human interaction, and tasks are being shuttled off to AI agents.

Enter the humble hobby. A thriving hobby economy might be the perfect fit for the AI-era — and offer some labor-market solutions for a workforce that’s having to pivot on the fly.

“The hobby economy supports people to really become highly skilled at something,” Lind said, “and it doesn’t necessarily mean that you have to graduate even from high school — not to mention college — in order to be somebody who is going to be leading a class on gardening or is going to be running a board game café.”

Tell us about your favorite analog pastime or hobby-based business by reaching this reporter at jkaplan@businessinsider.com.

Hobbies are part of the ‘productive leisure’ economy

Benjamin Chipman, a 24-year-old marketer and content creator in Brooklyn, has been trying out a bevy of hobbies — from Spanish language school to glass blowing to leatherworking. He loves trying out new things, especially as a post-graduate worker who misses classes and extracurricular activities. He has particularly gravitated toward classes and hobbies focused on scents and the art of perfume making, something he hopes to pursue professionally someday.

“It’s not an investment in anything other than in you. If you’re going to spend money on everything else and you have some sort of discretionary income — that’s going to support your mental health, that’s going to make you more productive at work because you’re not just thinking about work all the time,” Chipman said. “It gives you that respite, it gives you that break. It’s going to help you meet new people.”

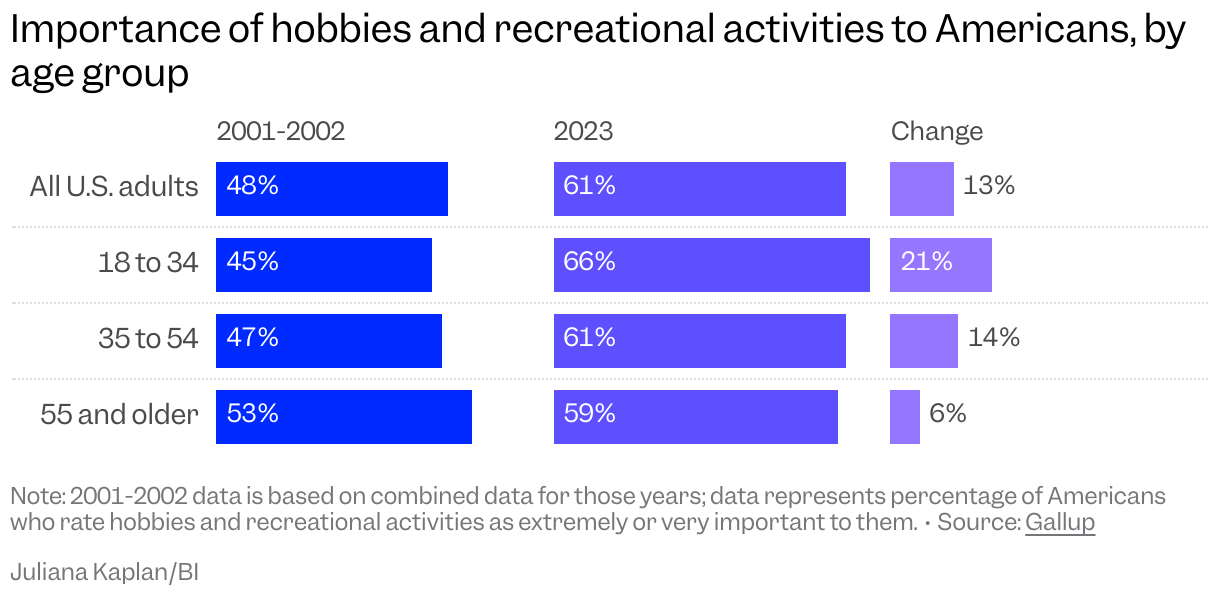

Chipman is part of a larger trend: As of 2023, a majority of American adults said in a Gallup survey that hobbies and recreational activities were extremely or very important in their lives, a 13 percentage point increase since 2002. That’s particularly pronounced among Americans 18 to 34. They’re turning toward analog bags stuffed with crafts as an alternative to doomscrolling. It’s all part of a broader Luddite-inspired movement among young people who are smashing iPhones, adopting dumb phones, and hosting anti-social media parties.

The sentiment comes as Americans face fewer third spaces, less time spent socializing, and a heftier price tag for nights out. As Chipman said, it feels more justifiable to put money toward a hobby class than going out; at least you’ll walk away with something worthwhile.

That’s a shift Lind has noticed, too: People aren’t leaving their homes as much as to engage with what she calls the “pure leisure” economy, which includes things like a nice meal, shopping, or a movie. Ironically, technological advances and disruptions have made it possible for all of these things to be done at home now. Instead, consumers might increasingly find it worthwhile to venture out for “productive leisure,” an experience that can’t be replicated at home or by the chatbot on their phones.

In an era when people especially value getting the most for their money, hobbies may be ripe for both spending and selling. IBISWorld projects that fabric, craft, and sewing supplies stores in the US will see their revenues grow from $5.3 billion to $5.8 billion by 2030, and revenue for online hobby and craft supplies sales will grow from $22.6 billion to $25.1 billion.

Abby Glassenberg, the president and cofounder of the Craft Industry Alliance, chalks up some of the recent hobby interest — especially in relation to a more digital world — toward a newer yearning for the tactile.

“I think one of the feelings that especially younger people have is that they don’t own anything. All their music is available on Spotify; you don’t buy a record or a CD, and you don’t have a physical collection of anything. It all lives in your phone,” Glassenberg said. “And I think that as a human, that doesn’t feel so good.”

By contrast, as Glassenberg said, crafting feels very real. You can see your mistakes and hold your end result — a far cry from an AI ecosystem that increasingly can create an intangible, alternate-screen-based reality. If the last few decades were about how easily something could be mass-produced, the pendulum of taste might swing back toward the handmade.

“I think that people are going to continue to really value real life and real life objects, and the beauty of handmade,” Glassenberg said.

What an AI-proof hobby economy means for jobs

In Lind’s vision, hobbies have a built-in advantage, providing a new economic foundation through consistency and spillover spending. As opposed to pure leisure, a rock climber, for example, hits the wall regularly. They’re spending money on instructors and at the café in the gym. In contrast, few people attend the movies every weekend; these are often one-off outings. Hobbies are designed to be purposefully iterative — something that could be a boon for downtowns and businesses nearby.

“That kind of recurring visitation is also really healthy for people using transit and supporting public transportation,” Lind said. “It also creates regular foot traffic, and it also potentially works better for people in that you may also end up spending a hundred dollars, but it’s not going to be across one night out, it’s going to be maybe five different times that you go back to the place.”

For the workers who keep the hobby economy afloat, it’s an opportunity to skill up beyond what traditional retail requires, without relying on traditional education. That specialization can also open up the door to new wage opportunities, leading to more dollars flowing through the areas where they live and work.

Of course, as Glassenberg notes, there are still serious headwinds facing hobbyists — the shuttering of major craft retailers like Joann’s and tariffs have packed a one-two punch for many retailers and crafters alike. That means there’s still a big gap between the vision of a hobby-forward AI future and the reality facing activity enthusiasts. Even so, though, optimists see an opportunity.

“I have spoken to a lot of our members who’ve said it is the most challenging time that they can remember. It’s a lot of different things going on,” Glassenberg said. “At the same moment, I think we’re grateful that the zeitgeist is turning toward handmade.”

Read the original article on Business Insider

The post The AI future doesn’t have to be grim: Get a hobby appeared first on Business Insider.